Thermocapillary Thin Film Flows: Periodic Steady States and Film Rupture

Research Seminar Institut Mittag-Leffler, Stockholm 2023

This is the manuscript of a blackboard talk. For the full result see https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.11279

Introduction

Modelling

We consider a thin liquid film of an

- incompressible

- viscous

- Newtonian

fluid on a solid heated plate such that

- capillary forces dominate (that is surface tension is the driving force of the dynamics).

Assumptions

- We assume that the free boundary is given by the graph of a function $h=h(t,x)$.

- We assume that the aspect ratio \(\varepsilon = \frac{H}{L} = \frac{\text{characteristic height}}{\text{characteristic length}} \ll 1\) is very small. This will allow us to derive a closed equation for the film height \(u\) via asymptotic analysis.

- We assume that the problem is one-dimensional, that is that the fluid is homogenenous in \(y\)-direction.

Henri Bénard observed in 1900 that regular polygonal – typically hexagonal – pattern emerge if the temperature difference between the heated solid bottom and the ambient air reaches a critical threshold. Even film-rupture states can emerge experimentally depending on the thickness of the film and the heat conduction of the ambient gas.

It took over 50 years to understand the reason behind this phenomenon and it was Block and Pearson who demonstrated that the Bénard cells do form due to the thermocapillary effect.

The thermocapillary effect says that due to the dependence of the surface tension on

temperature, temperature variations lead to (tangential) stress imbalances on the surface. Since, for most fluids, the surface tension is a decreasing function of the temperature, temperature imbalances generate flows of the fluid from warmer to colder regions, much as in the Marangoni effect. If this effect is stronger than the stabilising effect of surface tension, even small variations in the film height will be the cause of instability as the effect is self-reinforcing.

Mathematically, the problem is known as the Bénard–Marangoni problem and is usually modelled by the Boussinesq–Navier–Stokes system. This is a coupled system of the Navier–Stokes equations with a transport-diffusion equation for the temperature under the assumption that density variations due to buoyancy are negligible.

In the bulk region \(\{(t,x,z) \in \mathbb{R}_+ \times \mathbb{R}^2 : 0 < z < h(t,x) \}\) we have for \(u=(u_1,u_2)\):

\[\left\{ \begin{array}{rcl} \partial_t u+ (u\cdot\nabla)u & = & - \nabla p + \mu \Delta u - ge_z, \\ \operatorname{div} u & = & 0, \\ \partial_t T + (u\cdot \nabla) T & = & \chi \Delta T. \end{array} \right.\]and boundary conditions at the free boundary \(z=h(t,x)\):

- kinematic boundary condition: \(\partial_t h + u_1h = u_2\)

- stress-balance condition: \(\Sigma(p,u)n = \sigma \kappa n - (\partial_x T) \tau\) (here, \(n\) is the outer unit normal, \(\tau\) the tangential component, \(\sigma\) the surface tension, \(\kappa\) the curvature, and \(\Sigma(p,u) = - p\mathrm{Id} + \frac{1}{2} (Du+Du^T)\) is the Cauchy stress tensor)

- heat transfer condition: \(k\nabla T n = -k(T-T_g)\) (\(k\) is the heat conductivity of the fluid, \(K\) the heat exchange coefficient)

and at the fluid-solid interface \(z=0\):

- slip condition: \(u = 0\)

- heat transfer condition: \(T = T_s\)

Lubrication approximation

Rescaling the system by replacing \(x\) with \(\varepsilon x\) and \(t\) with \(\varepsilon^2 t\), we can obtain an asymptotic expansion in the aspect ratio \(\varepsilon\). By sending \(\varepsilon \searrow 0\), we obtain a closed equation for the film height

\(\partial_t h + \partial_x \Bigl(h^3(\partial_x^3 h - g\partial_x h) + M\frac{h^2}{(1+h)^2}\partial_xh\Bigr) = 0,\quad t>0,\ x\in \mathbb{R} \tag{1}\)

where \(g>0\) is a gravitational constant and \(M>0\) is the Marangoni number, which is proportional to the difference of the temperatures of the solid and the ambient gas.

Linear stability analysis

Since every constant height is a solution to equation (1), we may choose our favourite height \(\bar{h}=1\). Linearising about \(\bar{h}\) gives the equation

\[\partial_t w = \mathcal{L}w\]with linear operator

\[\mathcal{L}w = -\partial_x^4 w + \bigl(g - \tfrac{M}{4}\bigr)\partial_x^2 w.\]Plugging in the ansatz \(w=\exp(\lambda t - ikx)\), we obtain the dispersion relation

\[\lambda(k) = - k^4 + \bigl(\tfrac{M}{4} - g\bigr)k^2.\]At \(M = M ^*=4g\), the quadratic coefficient changes sign and the system undergoes a (conserved) long-wave instability. This suggests, for \(M>M^*\), that waves with wave number \(\vert k\vert \leq k_0=\sqrt{\frac{(M-M^*)}{4}}\) destabilise. We will be interested in the bifurcation of periodic patterns with the fixed wave number \(k_0\) at \(M=M^* +4k_0^2\). This discretises the spectrum and only waves with wave number \(k_0\) destabilise.

Goals

We will show

- the existence of a local bifurcation branch at \(M(k_0) = M^* + 4k_0^2\) consisting of \(\frac{2\pi}{k_0}\)-periodic even stationary solutions

- that this branch can be extended to a global bifurcation branch whose limit points exhibit film rupture

- show that limit points are weak even periodic stationary solutions

Hamiltonian formulation and local bifurcation branch

The main observation for the bifurcation analysis is that the stationary problem can be formulated as a Hamiltonian system.

Derivation of the Hamiltonian formulation

We study the stationary problem

\[\partial_x \Bigl((h^3(\partial_x^3 h - g\partial_x h) + M\frac{h^2}{(1+h)^2}\partial_xh\Bigr) = 0\]and rewrite this using \(h=\bar{h} + v = 1+v\) as

\[\partial_x \Bigl((1+v)^3(\partial_x^3 v - g\partial_x v) + M\frac{(1+v)^2}{(2+v)^2}\partial_xv\Bigr) = 0\]can be integrated once using that constant film heights are solutions:

\[(1+v)^3(\partial_x^3 v - g\partial_x v) + M\frac{(1+v)^2}{(2+v)^2}\partial_xv = 0\]Dividing by \((1+v)^3\), we may integrate again and obtain the second-order ODE

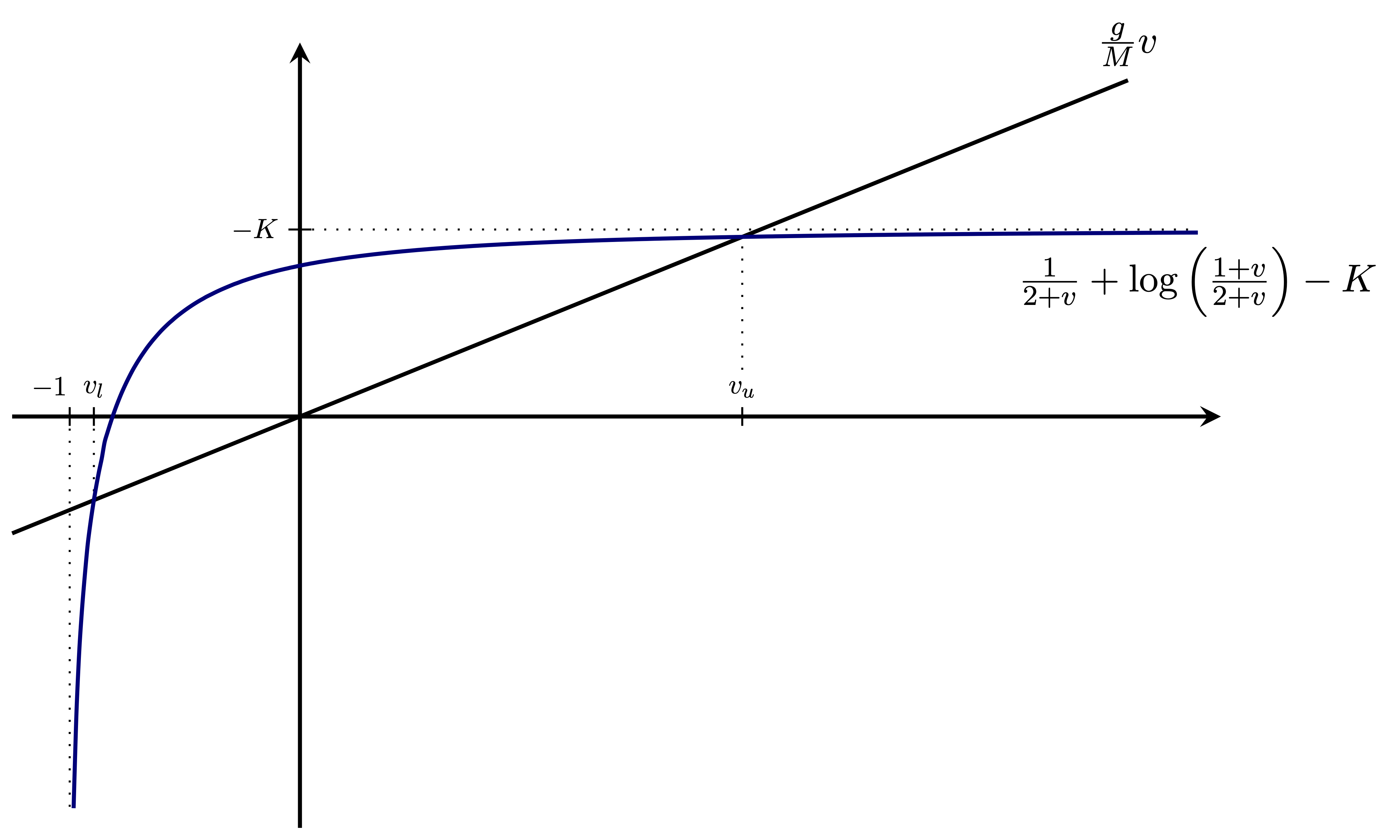

\[\partial_x^2 v = gv - M\Bigl(\frac{1}{2+v} + \log\Bigl(\frac{1+v}{2+v}\Bigr) \Bigr) + MK\]with constant of integration \(K\). Note that the vector field is singular at \(v=-1\) in accordance with the film height degenerating there. The corresponding first-order system is a Hamiltonian system given the Hamiltonian

\[\mathcal{H}(v,w) = \frac{1}{2}w^2 - \frac{g}{2} v^2 + M(1+v)\log\Bigl(\frac{1+v}{2+v}\Bigr) - MKv,\]where \(w= \partial_x v\).

Fixed points of the Hamiltonian system are given at \(\nabla \mathcal{H}=0\), hence \(w=0\) and \(v\) satisfies

If \(K< \tfrac{1}{2} + \log\bigl(\tfrac{1}{2}\bigr)\) or \(M \neq M^*\), there are two fixed points \(-1< v_l \leq 0 \leq v_u\). (Note that the range of \(K\) is necessary to obtain one negative and one positive fixed point.)

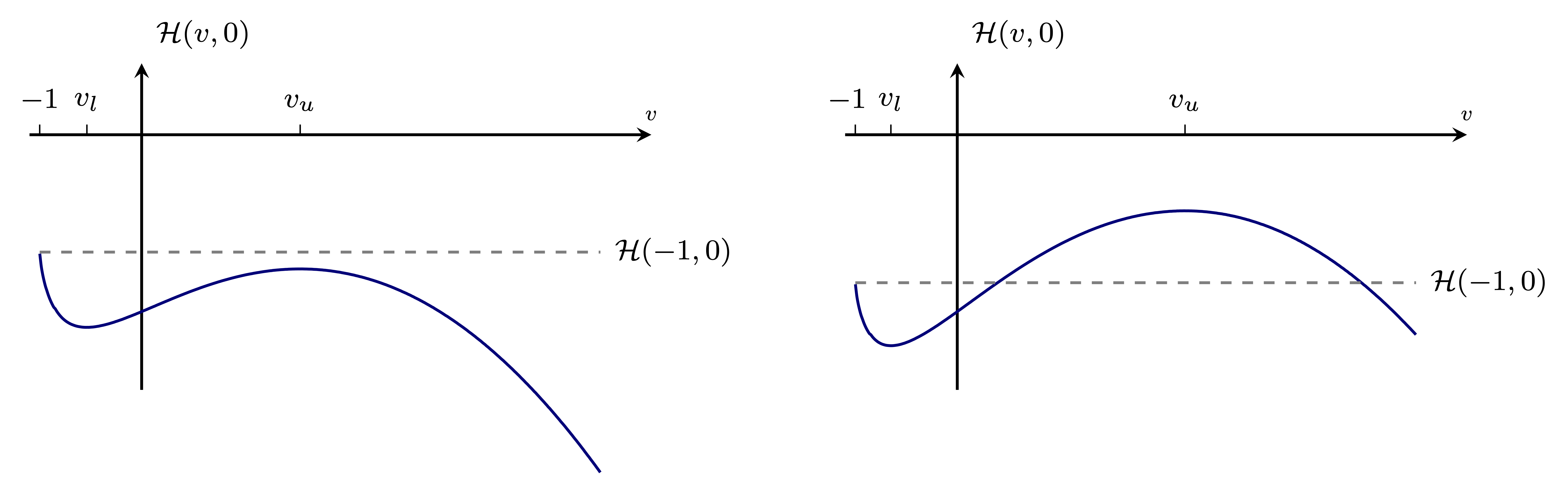

Observe that the dynamics do \(\mathcal{H}(v_u,0)\), as this is a saddle point and a homoclinic orbit only exists if \(\mathcal{H}(v_u,0)\leq \mathcal{H}(-1,0)\).

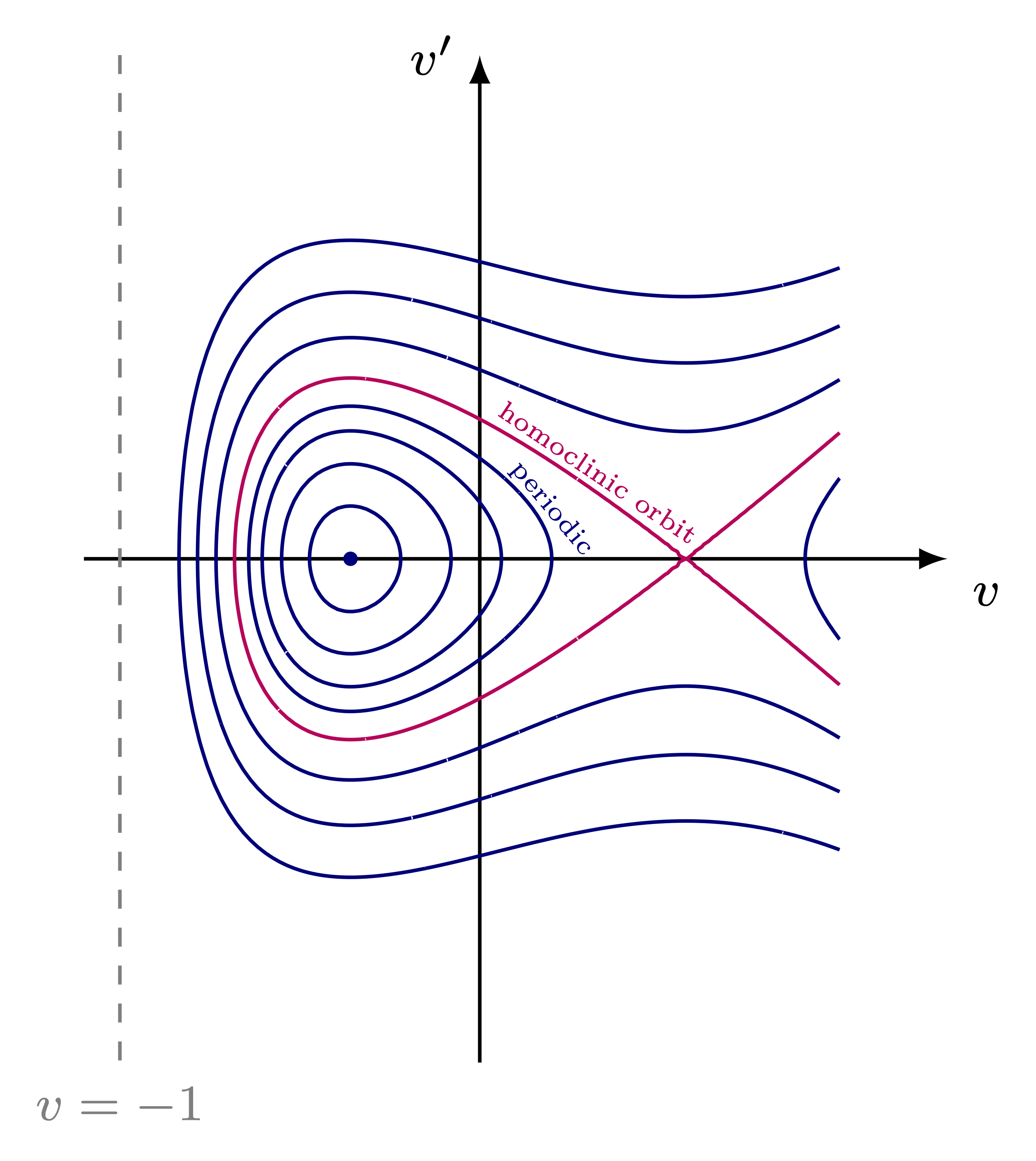

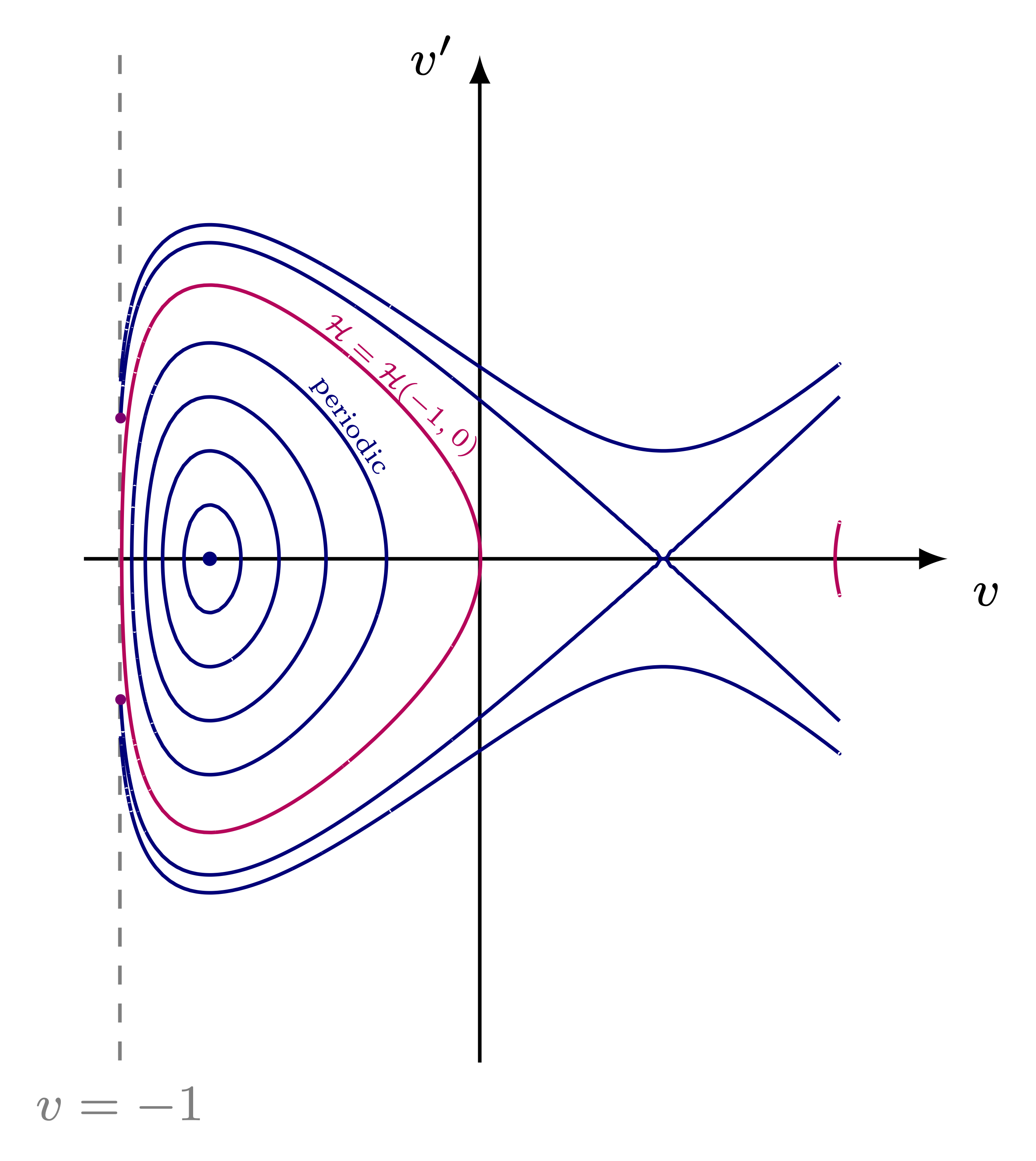

Phase plane analysis of the Hamiltonian reveals the following phase portrait:

We conclude

- \(v_l\) is a center and there is a neighborhood of \(v_l\) filled with periodic orbits

- \(v_u\) is a saddle point and provided \(\mathcal{H}(v_u,0) \leq \mathcal{H}(-1,0)\), there is a homoclinic orbit about \(v_u\)

- either this homoclinic orbit or the level set of \((-1,0)\) are the boundary of the set of periodic orbits

- if there is a homoclinic orbit, there is a blue-sky catastrophe, that is the period goes to \(+\infty\) as one approaches the homoclinic orbit

Local bifurcation

We now analyse the bifurcation of \(\frac{2\pi}{k_0}\)-periodic evenn stationary solutions at Marangoni number \(M = M^* +4k_0^2 > M^*\). We impose that the mass of the solution is conserved along a bifurcation curve, that is we impose

\[\int_{-\frac{\pi}{k_0}}^{\frac{\pi}{k_0}} v(x) \, \mathrm{d}x = 0.\]Define the bifurcation problem

\[F(v,M) := \partial_x^2v - gv + M\left( \frac{1}{2+v} + \log\left(\frac{1+v}{2+v}\right) \right) - MK(v)= \partial_x^2v + f_M(v) - MK(v) =0.\]That mass is conserved gives the condition on the constant of integration \(K(v)\):

\[K(v) = \frac{k_0}{2\pi} \int_{-\frac{\pi}{k_0}}^{\frac{\pi}{k_0}} \frac{1}{2+v} + \log\left(\frac{1+v}{2+v}\right)\, \mathrm{d}x.\]This definition asserts that \(F\) leaves spaces of functions with mean zero invariant.

To study the bifurcation problem, we define the following function spaces such that \(F\colon \mathcal{U}\times \mathbb{R}\to \mathcal{Y}\)

\[\begin{split} \mathcal{X} & = \{v\in H^2_{\mathrm{per}} : \int_{-\frac{\pi}{k_0}}^{\frac{\pi}{k_0}} v(x) \, \mathrm{d}x = 0,\, v \text{ is even} \}, \\ \mathcal{U} & = \{v\in \mathcal{X} : v > -1\},\\ \mathcal{Y} & = \{v\in L^2_{\mathrm{per}} : \int_{-\frac{\pi}{k_0}}^{\frac{\pi}{k_0}} v(x) \, \mathrm{d}x = 0,\, v \text{ is even} \}. \end{split}\]The restriction to even functions guarantees that the kernel of \(L=\partial_v F(0,M^*(k_0)) = \partial_x^2 + k_0^2\) is one-dimensional and \(\operatorname{ker} L = \operatorname{span}\{\cos(k_0x)\}\).

We can now apply the Crandall-Rabinowitz theorem to obtain a local bifurcation branch at \(M^*(k_0)\).

Theorem

Fix \(k_0 >0\). Then at \((0,M^*(k_0))\) a subcritical pitchfork bifurcation occurs and there exist \(\varepsilon >0\) and a branch of solutions

\[\{(v(s),M(s)) : s \in (-\varepsilon,\varepsilon)\} \subset \mathcal{U} \times \mathbb{R}\]to the bifurcation problem \(F(v,M)=0\) with expansions

\[\begin{split} v(s) &= s \cos(k_0 x) + \tau(s), \\ M(s) &= M^\ast(k_0) - \frac{(g+k_0^2)(8g+41k_0^2)}{12k_0^2} s^2 + \mathcal{O}(\vert s \vert^3), \end{split}\]where \(\tau = \mathcal{O}(\vert s \vert^2)\) in \(\mathcal{X}\).

Global bifurcation branch

Next, we want to extend the local bifurcation branch to a global bifurcation branch and describe its behaviour at infinity.

Theorem

Let \(k_0>0\) and

\[\{(v(s),M(s)) : s \in (-\varepsilon,\varepsilon)\} \subset \mathcal{U} \times \mathbb{R}\]the bifurcation branch obtained in Theorem \ref{thm:local-bifurcation}. Then, there exists a globally defined continuous curve

\[\{(v(s),M(s)) : s \in \mathbb{R}\} \subset \mathcal{U} \times \mathbb{R}\]consisting of smooth solutions to the bifurcation problem \eqref{eq:bifurcation-problem}, which is bounded in \(\mathcal{X} \times (0,\infty)\) and such that

\[\inf_{s\in \mathbb{R}} \min_{x\in \bigl[-\tfrac{\pi}{k_0},\tfrac{\pi}{k_0}\bigr]}v(s) = -1.\]To prove this theorem, we rely on analytic global bifurcation theory. This states that then local bifurcation curve can be extended to a global bifurcation curve if

(1) \(\partial_v F(v,M)\) is a Fredholm of index zero, whenever \(F(v,M) = 0\); (2) bounded, closed subsets \(\{F(v,M))=0\}\) are compact in \(\mathcal{X}\times \mathbb{R}\).

Moreover, at infinity, at least one of three conditions hold

(C1) blow-up: \(\|(v(s),M(s))\|_{\mathcal{X}\times \mathbb{R}} \longrightarrow +\infty\) (C2) solution approaches boundary of phase space \(\mathcal{U}\), i.e. \(\inf v(s) \longrightarrow -1\) as \(s\to+\infty\) (C3) \((v(s),M(s))\) is a closed loop

For (1), observe that \(\partial_v F(v,M) = \partial_x^2 \partial_x^{-2}\partial_v F(v,M) = \partial_x^2(\mathrm{Id} + R)\), where \(R\) is a compact operator and \(\partial_x^2\) is invertible from \(\mathcal{X}\to\mathcal{Y}\), and(2) follows by standard elliptic regularity theory.

Next, we rule out (C1) and (C3).

Nodal property

To rule out (C3), we use global bifurcation in cones. Define the cone

\[\mathcal{K} = \left\{v\in \mathcal{X} : v \text{ is non-decreasing in } \bigl(-\frac{\pi}{k_0},0\bigr) \right\}.\]The idea of the proof relies in showing a nodal property, that is, if \(v(s)\in \mathcal{K}\setminus\{0\}\), then \(v(s)\) must be strictly increasing in \(\bigl(-\frac{\pi}{k_0},0\bigr)\). If it is not strictly increasing, one can find \(x^*\in \bigl(-\tfrac{-\pi}{k_0},0\bigr)\) with \(v'(x^*)=0\). Since \(v\) is at the boundary of \(\mathcal{K}\), it must also hold \(v''(x^*)=0\). But then, differentiating \(F(v,M)=0\), we obtain the ODE

\[\partial_x^3 v + f_M'(v)\partial_x v = 0.\]Writing \(w=\partial_xv\), this has the initial conditions \(w(x^*)=\partial_xw(x^*)=0\) and hence \(w=0\), and so also \(v=0\) as the mass is fixed to zero.

Ruling out blow-up

Finally, we rule out (C1), that is blow-up of \(\|(v(s),M(s)\|_{\mathcal{X}\times \mathbb{R}}\). The proof is rather technical and we give a sketch of the proof.

Step 1: show by contradiction that film rupture must occur. Idea: if \(\inf_{s\in \mathbb{R}} \inf_{x} v(s) > c >-1\), this gives a lower bound for \(K\). An upper bound for \(M\) follows from proving that the maximal period of any periodic orbit tends to \(0\) as \(M\to+\infty\). This contradicts that solutions have a fixed period. A uniform bound for \(v(s)\) in \(\mathcal{X}\) then follows from standard elliptic regularity theory combined with a uniform upper bound of the upper fixed point, giving control of \(v(s)\) in \(L^{\infty}\). This would rule out both (C1) and (C2), a contradiction!

Step 2: Without any additional assumptions, prove that \(0< M_u <M(s)< M_l <\infty\) must be bounded above and below and \(-\infty < K_u < K\). Idea: if \(M\to + \infty\) or \(M\to 0\) or \(K\to-\infty\) show that all periodic orbits lie in \(-1<v <0\), a contradiction to the mass vanishing along the curve. This can be obtained from a rescaling argument in the Hamiltonian system.

Step 3: Prove uniform bounds for \(v(s)\) in \(W^{2,p}_{\mathrm{per}}\) for any \(1\leq p < \infty\). Idea: since we obtained uniform bounds \(M(s)\) and \(K(v(s))\), we also obtain uniform \(L^{\infty}\)-bounds for \(v(s)\). To obtain a uniform bound for the second derivative, it suffices to control \(\log(1+v(s))\) in \(L^p\) close to the minimum of \(v\). A lower bound for the second derivative follows again from the ODE, as the vector field explods as \(v\to -1\). Hence, \(v\) behaves at least quadratically around its minimum and we obtain

\[\int \log(1+v(s))^p \mathrm{d}x \lesssim \int \log(|x-x_{\mathrm{min}}|^2)^p \mathrm{d} x < \infty.\]Hence, \(v(s)\) is uniformly bounded in \(W^{2,p}_\mathrm{per}\) for any \(1\leq p <\infty\). This is optimal, since \(v(s)\) blows up in \(W^{2,\infty}_\mathrm{per}\) as the vector field blows up, when \(v \to -1\).

Film rupture

Finally, we show that any weak limit point of \((v(s))\) gives rise to a periodic, stationary weak solution to the thin-film equation that exhibits film rupture.

A weak stationary solution to (1) is a function \(h=h(x)\) such that

\[\int_{\mathbb{R}} \left(h^3(\partial_x^3h-g\partial_x h) + M\frac{h^2}{(1+h)^2} \partial_xh \right) \partial_x \varphi \, \mathrm{d}x = 0\]holds for all \(\varphi \in H^1(\mathbb{R})\) with compact support.

Take any weak limit point \(v_{\infty}\in \mathcal{X}\) of \(v(s)\) and define \(h_{\infty} = 1+v_{\infty}\). Since \(v(s)\) is smooth, \(h(s)=1+v(s)\) is a smooth solution to

\[\partial_x\left(h(s)^3(\partial_x^3h(s)-g\partial_x h(s)) + M\frac{h(s)^2}{(1+h(s))^2} \partial_xh(s)\right)=0.\]In particular, \(h(s)\) is a weak stationary solution. Hence, it suffices to show that the nonlinear flux

\[h(s)^3(\partial_x^3h(s)-g\partial_x h(s)) + M\frac{h(s)^2}{(1+h(s))^2} \partial_xh(s)\rightharpoonup h_{\infty}^3(\partial_x^3h_{\infty}-g\partial_x h_{\infty}) + M\frac{h_{\infty}^2}{(1+h_{\infty})^2} \partial_xh_{\infty}\]converges weakly in \(L^2_\mathrm{per}\) locally on compact subsets of \(\{h_{\infty}>0\}\). This follows after one obtains uniform bounds of \(\partial_x^3 h(s)\) in \(L^2\) locally on \(\{h_{\infty}>0\}\). Then, passing in the limit in the weak formulations, proves that \(h_{\infty}\) is indeed a weak, periodic, stationary solution which exhibits film rupture.